Yugoslavia’s nuclear program stands as one of the most intriguing and most controversial episodes in the history of the former Yugoslavia. Known as the Vinča program, after the institute where it was developed, it was part of a broader national effort to join the global nuclear race, primarily for the peaceful use of nuclear energy, but also for researching the military potential of nuclear weapons. Initiated in the context of Cold War tensions, this project was a pioneering venture in science and technology, yet it was also marked by serious incidents and political turbulence.

The Beginnings of the Yugoslav Nuclear Program

Yugoslavia’s nuclear program formally began in the late 1940s, in the aftermath of World War II, during a time when the country, under the leadership of Josip Broz Tito, aimed to establish technological and scientific independence. At that time, the global race for nuclear technology was in full swing, led by the United States and the Soviet Union, both promising virtually unlimited energy resources and military superiority to those who possessed nuclear weapons.

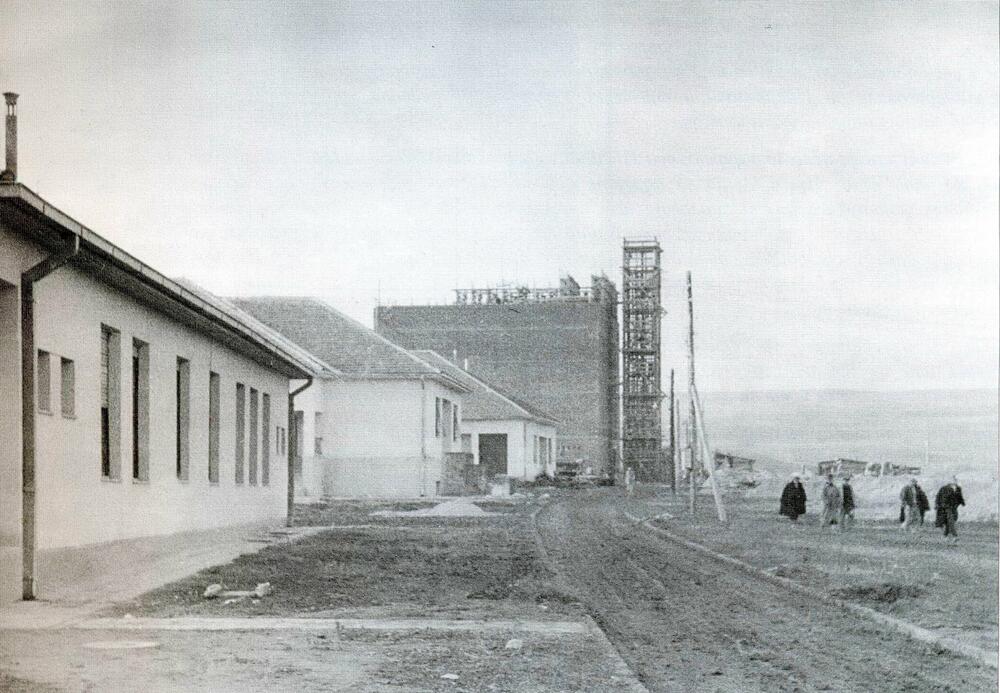

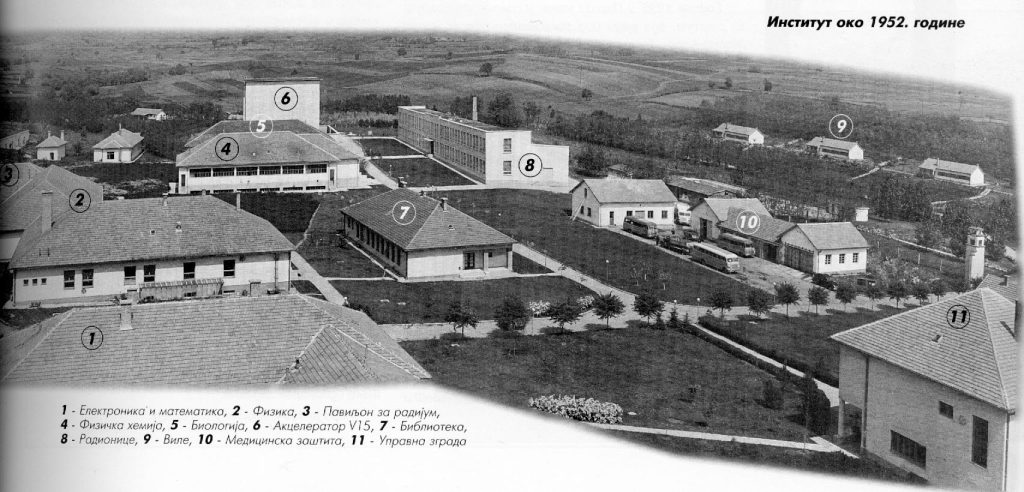

After breaking ties with the Soviet Union in 1948, Yugoslavia was forced to rely on its own resources and develop its own capabilities. Tito recognized the potential that nuclear technology could offer Yugoslavia, both in the military and civilian sectors. The Institute for Nuclear Sciences in Vinča, founded in 1948, became the central hub of the Yugoslav nuclear program.

“Vinča Institute”: The Heart of the Yugoslav Nuclear Program

The “Vinča Institute”, located near Belgrade, was established with the goal of advancing nuclear science and technology. Given that Yugoslavia was outside the influence of the major powers after its split with the Soviet Union, it was essential for the country’s scientific community to focus on independently developing nuclear capabilities. Vinča was built as a multidisciplinary research center, with a focus on nuclear physics, engineering, chemistry, and biomedicine.

Within the “Vinča Institute”, Yugoslavia developed its first nuclear reactors. The first reactor, known as the RA reactor, was a 6.5-megawatt research reactor, water-cooled and moderated with heavy water. It played a crucial role in conducting experiments and developing nuclear technologies for peaceful purposes, including the production of isotopes for medical and industrial use.

The second reactor, the RB reactor, was smaller and used for physical experiments with low-power neutron sources. These reactors laid the foundation for further nuclear research in Yugoslavia, but they also posed significant risks, considering the limited experience Yugoslav scientists had at the time in handling nuclear materials.

The First Incident at “Vinča” – The 1958 Nuclear Accident

Unfortunately, the research work at Vinča was not without serious incidents. On October 15, 1958, one of the most severe nuclear accidents in Yugoslavia and in the world at that time occurred. The incident took place during an experiment in the RB reactor, when a team of physicists attempted to conduct an experiment involving the control of a nuclear reaction.

During the experiment, an unplanned release of radiation occurred, resulting in the exposure of eight researchers. At the time, there were no adequate safety measures in place, and the experiment itself was highly risky. The scientists worked without protective suits and did not follow basic safety precautions. When the incident happened, they were exposed to high doses of radiation, which caused serious health consequences for many of them.

This incident marked the first time that individuals survived severe radiation sickness thanks to what were then experimental bone marrow transplant treatments, which were carried out in France. Although several scientists survived, many suffered long-term health consequences, and one of the researchers later died from complications caused by radiation exposure.

Political Implications of the Nuclear Program

Following the 1958 incident, the Yugoslav nuclear program faced a series of challenges. In addition to scientific and technical problems, there were also political pressures both domestically and internationally. Yugoslavia, which maintained independence from both major blocs during the Cold War, aimed to develop nuclear technology for peaceful purposes. However, Tito was fully aware that any ambitions toward developing nuclear weapons would attract international scrutiny and could provoke hostility from both Western and Eastern powers.

By the early 1960s, Yugoslavia had developed the capacity to produce nuclear fuel, as well as technologies required for uranium enrichment. However, the sources of funding and support were diverse. Some technologies came from Western Europe—primarily France and the United Kingdom, while at the same time, Yugoslavia maintained sporadic cooperation with the Soviet Union, particularly during the early stages of its nuclear development.

Yugoslavia and the Ambition for Nuclear Weapons

One of the most fascinating and controversial questions surrounding the Yugoslav nuclear program is whether Tito seriously considered developing nuclear weapons. Although Yugoslavia officially maintained that its nuclear energy program was strictly for peaceful purposes, there is evidence suggesting that certain segments of the program. Especially during the 1960s, explored the possibility of developing nuclear weapons.

According to some researchers, Tito believed that Yugoslavia needed to possess nuclear weapons in order to protect its neutral position during the Cold War especially amid rising tensions with the Soviet Union. He understood that being seen as a nuclear power would further strengthen Yugoslavia’s independence and enhance its international standing.

Some sources suggest that the Yugoslav nuclear program reached a stage where it was capable of producing fissile material sufficient to build a nuclear bomb. However, political and economic pressure from abroad, particularly from the United States and other Western nations ultimately led Tito to abandon those ambitions.

Non-Proliferation Agreements and the Shift Toward Peaceful Projects

In 1968, Yugoslavia signed the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), formally ending all speculation about the potential development of nuclear weapons. With this agreement, Yugoslavia committed to using nuclear technology exclusively for peaceful purposes, including energy production and scientific research.

After signing the treaty, the Yugoslav nuclear program shifted its focus to the development of nuclear power plants. The largest project was the construction of the Krško Nuclear Power Plant in Slovenia. The plant, which began operating in 1981, was a joint venture between Slovenia and Croatia and represented the pinnacle of Yugoslavia’s ambitions in the field of civilian nuclear energy.

The Post-Tito Era and the Fate of the Program After Yugoslavia’s Dissolution

After the death of Josip Broz Tito in 1980, the Yugoslav nuclear program gradually lost momentum. The country’s economy was increasingly in crisis, and political instability among the federal republics made it difficult to sustain ambitious scientific and technological initiatives.

During the 1990s, with the breakup of Yugoslavia, programs like those at Vinča suffered serious setbacks. The Krško Nuclear Power Plant continued operating, but the Vinča Nuclear Research Institute significantly reduced its activities. Nevertheless, Vinča remained an important center for nuclear research in the post-Yugoslav period and continues to play a key role in Serbia’s nuclear projects today, with a focus on the peaceful use of nuclear energy.

The Yugoslav nuclear program at Vinča was a pioneering project that had a major impact on the development of science and technology in the country and beyond, on the international stage. Although the program was marked by incidents such as the 1958 accident, it stands as one of the key examples of independent technological development during the Cold War era.

While there was speculation about the potential development of nuclear weapons, Yugoslavia ultimately chose the path of peaceful nuclear energy. The programs at Vinča and Krško remain lasting testimonies to the technical and scientific ambitions of Yugoslavia, while incidents like the one in 1958 serve as reminders of the dangers faced by those working with nuclear technologies. Today, Vinča remains a symbol of Yugoslavia’s scientific vision and a part of the nuclear history of the Balkan region.

Thank you for reading,

Team Malamedija